crime and punishment

ac writes: an extended review of the novel. on redemption, religion, and the connection between illness and guilt.

let me just get this out of the way now: yes, i feel very pretentious for saying ‘ah yes here is my review of dostoevsky’s novel. not only because it proves to you that i read it but that i can critically think about it too.’ trust me, i already know. it seems, though, that i do not care. i had no inspiration to write this week and, when considering why that was, i realized that it was because i cannot stop thinking about this book!!

there are spoilers in this review, just by the way

dostoevsky’s 1866 novel paints the picture of the gothic and dilapidated city of st. petersburg. the streets are gloomy, full of misanthropic characters struggling with their vices and, often, their finances. our protagonist (if that is the word you want to use) is raskolnikov, an intelligent ex-student who spends his days isolated and alone within his cramped apartment. in part to ease his financial burden, but also for a myriad of psychological reasons, raskolnikov murders a pawnbroker alyona ivanovna and, out of necessity, her sister lizaveta. the majority of the novel follows raskolnikov’s worsening mental and physical state as he grapples with his guilt (arguable) and realizes his crime may not have been as seamless as he once believed it.

i read this novel for a book club that i am a part of, one that frequently challenges me to expand the limits of my perception of what i am reading and brings back similar joy to what i experienced in my favorite literature classes. at first, i was incredibly nervous to pick up this book (as i frequently am when it comes to ‘classics’). i’ve forayed into Russian literature briefly in the past with short stories by chekhov and tolstoy, but to open a real, pure novel translated from nineteenth-century Russian for the first time was, in short, daunting. and i definitely will admit that i struggled with the language and density of this novel when i was starting. within the first lines, the reader is separated from raskolnikov. there is no illusion that we are watching him from a distance, observing his behavior as a way to (i think) critique our own.

“at the beginning of July, during an extremely hot spell, towards evening, a young man left the closet he rented from tenants in S—y Lane, walked out to the street, and slowly, as if indecisively, headed for the K—n Bridge. He had safely avoided meeting his landlady on the stairs… And each time he passed, the young man felt some painful and cowardly sensation, which made him wince with shame.”

if you know me, you know that i have a fascination with illness in literature and the metaphor that it, often, represents. by far one of my favorite parts of the novel, dostoevsky creates a symbiotic relationship between one’s mental and physical health. as raskolnikov’s paranoia over being discovered for the murder begins to take over his psyche, he falls into a fit of “delirium,” forced out of his self-imposed isolation and into the care of others who are concerned for and, occasionally, suspicious of his well being. there is a clear connection not just between illness and crime, but that one’s guilt or conscience can be the catalyst for disease.

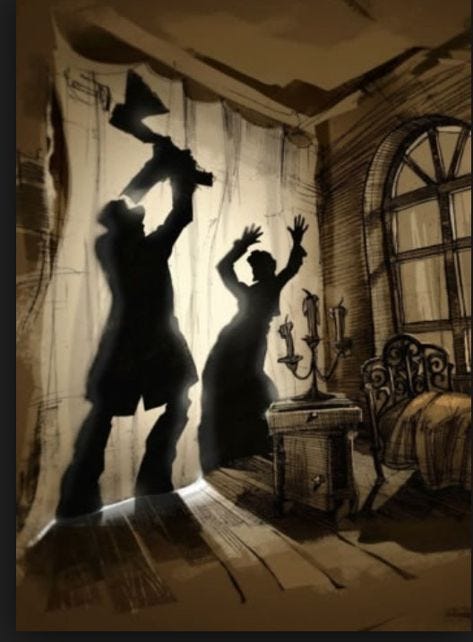

one of my favorite scenes throughout the entire novel is the murder itself. we are given intricate details of raskolnikov’s thought process as he meticulously plans every aspect of his crime. each moment keeps you on the edge of your seat, feverishly turning the pages to learn whether he will successfully murder alyona. what remains with me in retrospection, though, is the change in raskolnikov’s (and therefore the reader’s) perception of the crime. leading up to it, and immediately, raskolnikov is diligent in checking off all of his mental boxes to ensure he is not a suspect. however, as the novel continues, we begin to learn that there were more holes in his plan than it originally seemed, and raskolnikov’s illness increases his paranoia and, frequently, almost gives him away.

“he was not fully conscious when he entered the gates of his house; at least he did not remember about the axe until he was already on the stairs. and yet a very important task was facing him: to put it back, and as inconspicuously as possible. of course, he was no longer capable of realizing that it might be much better for him not to put the axe in its former place at all, but to leave it, later even, somewhere in an unfamiliar courtyard.”

crime and punishment, in a nutshell, is a conversation about redemption: if it possible, for whom is it possible, and how we can achieve it. the majority of the novel is cloaked in the dark atmosphere and nihilistic philosophy of the characters. we see raskolnikov’s sister enter into an engagement with the worst guy ever due to his financial security and ability to provide for the family. we see marmeladov, an ex-official, unable to save himself from his alcoholism. every character in the novel is tortured in their own way, a ‘sinner’ to put it biblically. yet, as we turn to the final chapters, in the distance we see the faintest hint of hope.

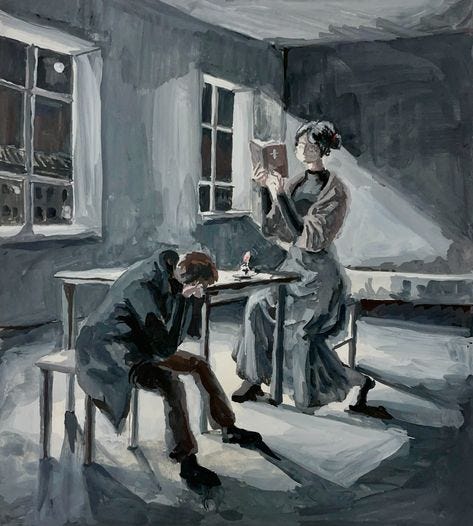

what by far stands out to me the most in this novel is dostoevsky’s use of religion. russian orthodox permeates throughout the story and, in its majority, we see raskolnikov struggle with his own beliefs. in the pits of his despair, it appears as though he has no religion. but he is drawn to the devout sonya, a woman who despite her occupation as a sex worker, maintains her faith.

in part four, raskolnikov begs sonya to read the story of lazarus from the new testament. lazarus was raised from the dead by jesus and brought back to life, a moment showing the power of the messiah and encouraging many to believe in him. one of raskolnikov’s main philosophies in crime and punishment is the belief that there are some individuals who are meant to be ordinary and some who are meant to be extraordinary. the latter of these groups, in his opinion, supersedes all societal rules. as he says to porfiry petrovich:

“in my opinion, if, as the result of certain combinations, kepler’s or newton’s discoveries could become known to people in no other way than by sacrificing the lives of one, or ten, or a hundred or more people… then newton would have the right, and it would even be his duty, to remove those ten or a hundred people”

for almost the entire novel, raskolnikov fancies himself to be a part of this group extraordinaries: the napoleon’s of the new world. which makes the story of lazarus so enticing when it comes merely a few chapters after this conversation. by raising lazarus from the dead, jesus is rewriting the laws of nature and thus proving himself to be one of raskolnikov’s ‘extradordinaries.’ however, he rises to this status without killing someone else, unlike raskolnikov. rather than encourage death to further his message, he subverts it. therefore, the story shatters the view raskolnikov maintains of the world around him, proving both his ordinariness and his fundamental misunderstanding of what makes a person extraordinary in the first place.

at the end of the novel, as raskolnikov sits in prison after confessing to the murders, the narrator takes note that the bible in his hands is not only the one owned by sonya, but it is the same copy “from which she read to him about the story of Lazarus.” in his final pages, dostoevsky reminds us of jesus’ extraordinariness and the possibility of rebirth. raskolnikov has faced the hard truth that he is not one of these ‘superiors’ and considers turning to religion for some new method of freedom.

“can her convictions not be my convictions now? her feelings, her aspirations, at least…”

i do not believe that dostoevsky’s argument is simply that rebirth comes from a belief in religion. rather, he uses russian orthodox christianity as the medium throughout crime and punishment to explain that redemption and ‘new life’ comes through community and generosity. raskolnikov spends almost all of the novel isolating himself from the people around him. he pushes away his family, his only real friend, and frequently feels disgust within himself when touched or comforted by other people. as the novel comes to a close, he admits to himself that he is truly in love with sonya and allows her to hold him. he physically opens himself up and shows the vulnerability that he has repressed for so long.

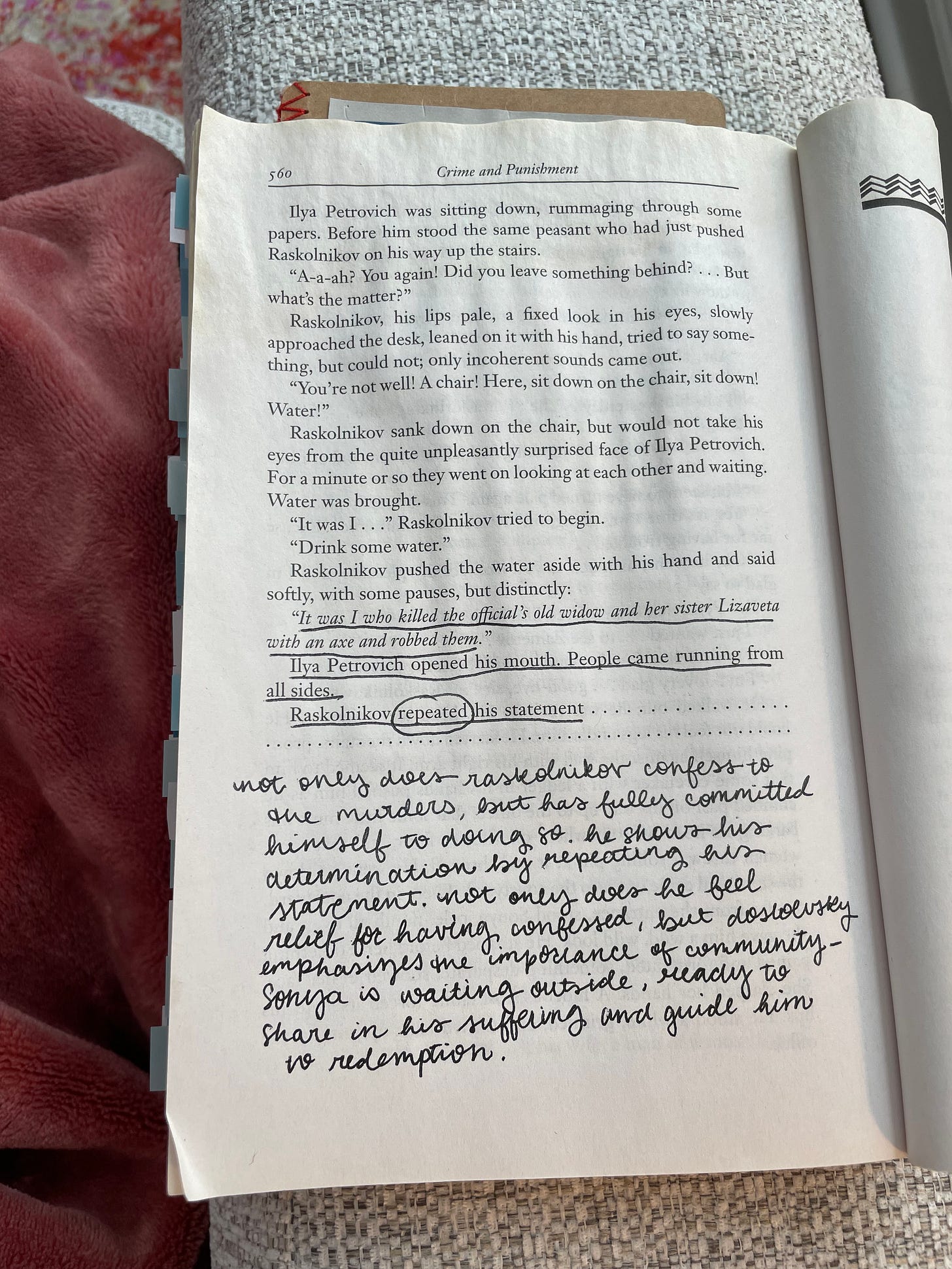

there has been some debate, including within myself, as to whether or not the epilogue was necessary to include within this story. the final chapter of part six ends with raskolnikov’s confession, the final antidote to his perpetual, guilt-induced illness. had the novel ended there, i believe the same level of ‘hope’ expressed at the end of the epilogue would have still been present. raskolnikov takes the first step towards redeeming himself. he comes to petrovich himself rather than waiting for his inevitable arrest. but i understand the appeal of the epilogue as a chapter which ties the loose ends left in the story and clarifies raskolnikov’s fate.

dostoevsky shows us that there is no such thing as a purely good or purely evil person, a fairly trite claim i know. but, as someone in my book club pointed out: "if dostoevsky really thought that people were black and white, he would not have been able to write this book.” the nuances in each character allow us to question what their real morals were, and the novel leaves us with a vague sense of optimism that no matter how depraved we believe ourselves to be, we can find our way out.

One of my favorite books! Love your take on it